Sometimes the decisive turn in a tax resistance campaign has come when the resisters have coalesced into a formal group with the authority to organize and coordinate resistance actions. Today I’ll give some examples of this.

- The Great Confederated Anti-Dray and Land Tax League of South Australia formed in the to fight taxes associated with a recently-enacted Road Act, and, once organized, the League was successful in its fight. Organizer Jonathan Norman remarked to a meeting of the League in : “They had before them an example of what might be achieved by union. In everything they had been victorious; the dray-tax. which from time to time was threatened to be enforced, was ultimately abandoned altogether. The various memorials from the different hundreds, backed by the memorial of the united delegates, had caused the Government to introduce an amended Act, which promised almost everything they desired.”

- When Charles Ⅹ and his ministers threatened to bypass the elected

legislature and start taxing and spending on their own initiative in

, French liberals declared that since

such actions violated the constitution, the people were under no

obligation to pay for them with their taxes. Taxed landholders in Brittany

formed the “Breton Association” to coordinate their resistance.

This Association had a two-fold object. They proposed, in the first place, to refuse to pay any illegal tax, and in the second place to raise by contribution a common fund for indemnifying any subscriber, whose property or person might suffer by reason of his refusal.

The association enacted a trigger mechanism for an organized tax strike and a process for collecting and distributing a mutual insurance fund. In this way they were able to present a credible threat to the planned royal usurpation — so much so that the newspapers that dared to print the Association’s charter were prosecuted and their editors imprisoned. This only served to fuel the movement: “The associations spread over the greater part of the kingdom; they embraced more than half the Chamber of Deputies, and a very considerable number of peers.”The members subscribed each ten francs. In the event of any tax being imposed without the consent of the Chambers, or with the consent of a Chamber of Deputies created by any illegal alteration of the existing law, payment of the tax was to be refused, and the money subscribed was to be employed in defending and indemnifying the persons who should so refuse, and to prosecute all who might be concerned in the imposing, or the levying of such illegal taxes.

- The Rebeccaites formed Farmers Unions which met in secret to discuss the same sort of grievances that, in disguise, Rebecca and her sisters would address vigilante-style, and which corresponded with each other in a regional network. One farmer said: “This Union among us is a very excellent thing if all join. When they elect members of Parliament they do just as they please, and we have no voice, but here we have. There is no way of putting things to rights till we get up this Union, and then we can do as we please and think best. If we had had this Union many years ago we should be better off than we are now!”

- The Women’s Tax Resistance League formed in when about twenty women from existing suffrage groups came together in London “with the single-minded aim of starting ‘an entirely independent society quite separate from any existing suffrage society with the object of spreading the principles of tax resistance.’ ” League organizer Margaret Kineton Parkes explained that it “included Suffragists from every camp, Conservative, Liberal, Socialist, as well as non-party, and was making every effort to get a large number of influential women to refuse to pay taxes” because “[t]he isolated refusal to pay was ineffective and only caused trouble to the refuser; but a large and unexpected number would cause considerable trouble to the Government and would bring the question at issue home to them.”

- Elias Rishmawi was among those who organized tax resistance in Beit Sahour during the first intifada. He remembers how important it was to have formed a network of committees so as to distribute communication and decision-making in anticipation of Israeli military disruption by means of curfews and arrests of the resistance leadership.

- Direct action-oriented pacifists in the United States came together in to form Peacemakers. “[T]his is not an attempt to organize another pacifist membership organization, which one joins by signing a statement or paying a membership fee,” they announced. By the group had about 2,000 members, about 150 of which were resisting taxes. A second group, War Tax Resistance, promoted the tactic within the anti-Vietnam War activist community. In , the National War Tax Resistance Coordinating Committee formed to help a variety of groups that included war tax resistance as part of their work to coordinate and share resources and expertise.

- During the Great Depression in the United States, taxpayers’ leagues, some of which organized property tax strikes, proliferated in the thousands. Such groups “spring up like mushrooms,” one critic complained, “every time you go out in the morning, you find more of them.” These leagues attacked the taxes on multiple fronts — not only organizing tax strikes but also coordinating legal suits and pressuring political figures.

- A proposed sales tax boycott in Ottawa in was boosted by the group Human Action to Limit Taxes. “As individuals we are lost,” one resister said. “But as a group we would have some impact.”

- In the Birmingham Political

Union of the Middle and Lower Classes formed. It would play a strong

role — and would advocate tax resistance — in the battle to pass the Reform

Act of . But it also began as a war tax

resistance group, asking its members to sign the following oath:

That in the event of the present ministers so misconducting the affairs of the country as to make it probable we shall be involved in a Continental war [with Belgium], we will consider the propriety of checking so mischievous an event by withholding the means as far as may lay in our power, and will then consider whether or not refusing to pay direct taxes may not be advisable.

- Similarly, the Catalonian “National Union” began life as a committee to direct a tax resistance action in and grew into the organizing party for an ambitious reform movement: “its demands included the entire reorganization of the vital forces of the nation: fiscal and administrative reform, the amelioration of the judicial system, the introduction of an effective system of compulsory education, the improvement of the provincial governments.”

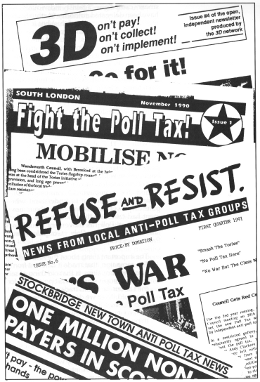

- In Danny Burns’s book on the Poll Tax Rebellion, he stresses how

important it was for the success of the campaign that people formed and

ran their own small-scale, neighborhood resistance groups, rather

than ceding control of the movement to the various established left-wing

partisan and labor-union groups who wanted to use the movement to their

own ends but were also afraid to identify themselves too closely with

the law-breaking resisters.

However, he also notes:Prior to the Anti-Poll Tax campaign, many people’s only experience of politics was a traditional Labour Party or trade union meeting — the sort of meeting where the top table takes up 90% of the discussion; where the only items discussed are those decided by the executive committee; where half the meeting time is spent discussing procedural motions or the order of words in a resolution; where political factions throw rhetoric across the room in angry and unproductive exchanges. Essentially, boring meetings which stretch long into the night. Hundreds of thousands of people have been to these meetings just once and never returned. To engage people in a mass campaign, the Anti-Poll Tax Unions had to challenge this culture of organisation. They had to make people feel wanted and included and give everyone a sense that they had a role.… This immediate form of organisation also meant that people weren’t patronised by those who had political experience. In the local groups, people didn’t need permission to act, they just had to get on the phone to their neighbours and get something going. People stay involved in political campaigns if they can contribute in the way that they feel is most effective. Very often this is not by sitting in boring meetings.

…most of the successful Anti-Poll Tax Unions operated on a principle of parallel development. Rather than trying to assert majority control or spend hours reaching consensus, people were allowed to get on with what they thought was most important. Everything could be done in the name of the Anti-Poll Tax Union, which existed to coordinate activity against the Poll Tax, not to specify its exact nature.

…it was sometimes in the places where the Anti-Poll Tax Unions were weakest that resistance was strongest. For example, St. Pauls was almost the only area in Bristol which couldn’t sustain an Anti-Poll Tax group. Local people didn’t feel the need to set up new groups because, as in many inner city areas, they already had strong networks of solidarity, and there was already a high level of general hostility to officials of any sort. … By the end of , three times as many people had turned up to court to contest their cases from St. Pauls than any other area.

- White supremacists in Louisiana met in to form “The People’s Association to Resist Unconstitutional Taxation” to coordinate their resistance to state and city taxes enacted by the reconstruction government there, and to provide legal support for resisters.

- Property owners of Silver Lake Assembly met in to decide how to respond to a property tax they felt was being illegally put over on them by a government with no authority to do so. They decided to respond as a group, “and perfected an organization for the purpose,” issuing a resolution saying that they “individually and collectively will resist the payment of the so-called taxes.”