|

Harry Reichenbach is best known for the publicity stunts he used to bring

crowds into early B-movies:

- Setting apes and lions loose in big name hotels to get the

Tarzan movies mentioned in the press.

- Hiring a woman to fall into a “trance” after viewing one

spooky film, then making sure there was enough rampant speculation

about whether movies could hypnotize people that everyone wanted to

try it out.

- Having actors pose as a Turkish rescue party coming to the

U.S. to return a young woman who

had eloped with an American soldier to her scheduled royal wedding.

Allegedly hush-hush, details of this mission were leaked to the eager

media, whose scoops turned into big publicity for the upcoming film

The Virgin of Stamboul.

But he describes what was perhaps his most poetic hack in the book

Phantom Fame:

I applied for work at a small art shop that had printed a lithograph of a

nude girl standing in a quiet pool. The picture sold at ten cents apiece

but nobody would buy it. I could earn my month’s rent if I had an

idea for disposing of the two thousand copies in stock. It occurred to me

to introduce the immodest young maiden to

Anthony Comstock, head of

the Anti-Vice Society and arch-angel of virtue. At first he refused to

jump at the opportunity to be shocked. I telephoned him several times,

protesting against a large display of the picture which I myself had

installed in the window of the art shop. Then I arranged for other people

to protest and at last I visited him personally. “This picture is

an outrage!” I cried. “It’s undermining the morals of

our city’s youth!”

When we arrived in front of the store window, a group of youngsters I had

hired especially for this performance at fifty cents apiece, stood

pointing at the picture, uttering expressions of unholy glee and making

grimaces too sophisticated for their years. Comstock swallowed the scene

and almost choked. “Remove that picture!” he fumed, and when

the shopkeeper refused, the Anti-Vice Society appealed to the courts. This

brought the picture into the newspapers and into fame. Overnight, the

lithograph that had been rejected as a brewer’s calendar, became a

vital national issue. Songs were written about it, actors wisecracked about

it, reformers denounced it, and seven million men and women bought copies

of it at a dollar apiece, framed it and hung it on the walls of their

homes. The name of the picture was “September Morn.” There

was no more immorality or suggestiveness to it than sister’s

photograph as a baby in the family album.

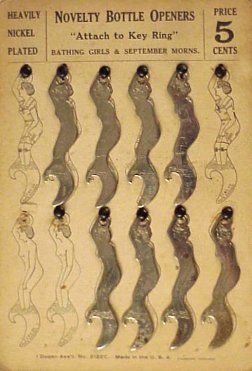

The painting, by Paul Chabas, went from being “rejected as a

brewer’s calendar,” to being, for a time, a celebrated icon on

par with the Mona Lisa. Curtis MacDougal, in Hoaxes, writes

that there “were ‘September Morn’ dolls, statues,

calendars and umbrella and cane heads; sailors

had the modest, shivering damsel tattooed on their hairy chests and amateur

artists drew their versions on bathroom floors,” to which

another commentator adds: “postcards,

candy boxes, cigar bands, cigarette flannels, pennants, [and]

suspenders.”

MacDougal ends by saying that “the most controversial nude of modern

times went on public exhibition in the Metropolitan Museum of Art”

in Manhattan where it can be seen to this day.

|

|