One of the recurring issues that comes up today in debates about conscientious tax resistance is whether (and if so, to what extent) paying taxes makes you liable for what the government does with the tax money. Does a taxpayer bear some responsibility, and deserve some blame, for paying taxes?

I’ve heard answers at either extreme: that taxpaying makes the taxpayer absolutely complicit in all of the government’s deeds, or that because the government forces you to pay taxes against your will you can’t be thought to be responsible for the consequences of paying them. For example, the blogger FSK wrote:

On the other hand, John T. Kennedy once argued to me:

(See also The Picket Line of for an in-depth look at many of the arguments that have been given concerning the question: does taxpaying make you complicit?)

Much of the debate concerns the extent to which taxpaying is a chosen, deliberate act of free will, or the extent to which it is a forced act done only under duress. On the one hand, taxpaying is certainly coerced — thus all of the various criminal and civil sanctions brought to bear against people who don’t pay up. On the other hand, these various sanctions are really just consequences of the choice you make, and all choices of any moral significance have consequences — the trick to being a good person is weighing these consequences well.

In the opening section of the third book of The Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle begins to take on the task of distinguishing the voluntary and involuntary, the chosen and unchosen, and such categories. As I go through the sections of this book I’ll be trying to see how taxpaying fits in to the system he devises.

(Note: some translations break this opening section out into three distinct sections.)

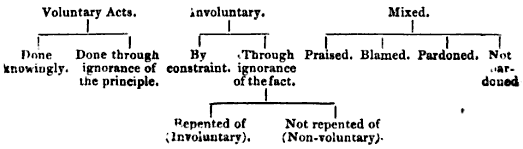

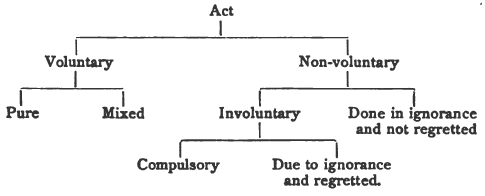

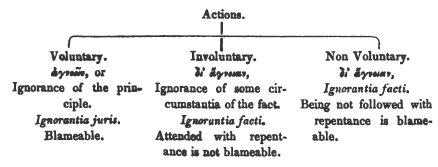

Aristotle says that distinguishing between the voluntary & involuntary is essential for a discussion of ethics, because only voluntary acts are rightly subject to praise or blame, honor or punishment. (Involuntary acts are due pardon or pity at worst.)

Voluntary acts are those that are caused by something internal to a person — that person’s will or desire or choice. Involuntary acts are caused or impelled from outside. That’s fine for the black-and-white cases, but there’s a big grey area.

As Aristotle has argued before, we are motivated in our actions by desire for pleasure and fear of pain. Do those things amount to compulsions that make our actions involuntary? Aristotle says no. To admit such an argument would be to make the voluntary/involuntary distinction meaningless. The desire for pleasure and fear of pain are internal to us and so represent voluntary impulses. This is true also for more extreme emotions like passion and anger.

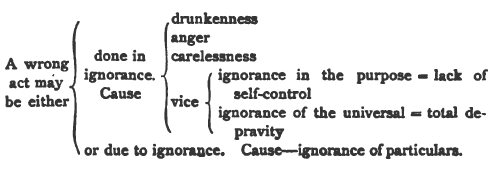

What if you do something wrong because you were ignorant about what you were doing or what the consequences would be? Aristotle says that actions done in ignorance form a third category: the “non-voluntary.” If the actor later is pained by the action and regrets it, it can then be promoted out of this purgatory into the involuntary category.

But isn’t everyone who acts wrongly acting in ignorance of how and why they ought to act rightly? Aristotle says that it is true that ignorance is what causes people to be unjust and wicked, but that this sort of ignorance does not change the voluntary/involuntary nature of the action: only ignorance of the particulars of the action, like what it is or what it is affecting. He gives the example of someone who is demonstrating the use of a weapon, thinking it to be disarmed, who fires it and inadvertently causes damage.

Illustration showing the varieties of ignorance that affect people’s voluntary actions, from St. George Stock’s paraphrase ()

What if you’re forced to do something vicious by fear of adverse consequences for not doing it — a lesser-of-two-evils sort of choice? Aristotle says that such acts are voluntary in-and-of themselves, “although in the abstract they may be said perhaps to be involuntary, as nobody would choose any such action in itself.”* He notes that you can be praised for putting up with degrading or painful circumstances for honorable ends, so why shouldn’t you be blamed for avoiding pain for dishonorable ends?

(But what if you voluntarily put yourself into a situation in which you know it is likely that you will have to make a lesser-of-two-evils sort of choice, I wonder?)

You may be pardoned for voluntarily doing an act “under pressure which overstrains human nature and which no one could withstand,” but there are some acts that you should prefer death to committing. In general you need to do a cost/benefit analysis.

So where does taxpaying fit in? So far it looks to be in this voluntary in-and-of itself but possibly involuntary in-the-abstract category. Aristotle hasn’t told us much about this category yet, so it’s hard to draw any conclusions about what this means.

Illustration showing Aristotle’s division of actions from R.W. Browne’s translation ()

Illustration showing Aristotle’s division of actions from St. George Stock’s paraphrase ()

Illustration showing Aristotle’s division of actions from John S. Brewer’s version ()

* Since this may be important, here are some other translations of this phrase:

- “Actions of this kind, therefore, are voluntary — though regarded independently of their surroundings they are surely involuntary: no one, that is, would make choice of an act of great sacrifice for its own sake.” (Walter M. Hatch)

- “Such acts, then, are voluntary, though in themselves [or apart from these qualifying circumstances] we may allow them to be involuntary; for no one would choose anything of this kind on its own account.” (F.H. Peters)

- “I have called them mixed acts as though they were partly voluntary and partly involuntary — involuntary as being acts such as no one under ordinary circumstances would do, but voluntary as proceeding from the will of the agent under the pressure of circumstances. But if you look closely into these acts, you will find that they are really voluntary.” (St. George Stock’s paraphrase)

- “Simply considered, however, they are perhaps involuntary; for no one would choose any one of these on its own account.” (Thomas Taylor)

Most other translations I looked at were pretty close to the wording I used in the main body, from William David Ross’s translation.

Index to the Nicomachean Ethics series

Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics

- Introduction

- Book Ⅰ

- Book Ⅱ

- Book Ⅲ

- Book Ⅳ

- Book Ⅴ

- Book Ⅵ

- Book Ⅶ

- Book Ⅷ

- Book Ⅸ

- Book Ⅹ

- Bibliography