In the eighth section of the sixth book of The Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle takes a closer look at practical wisdom, and its relation to the political arts, to universal and particular knowledge, and to intuition.

Practical wisdom, or prudence (phronesis), is one of the five faculties by which people can grasp the truth. Aristotle covered it in section three of this book, where he said that it is a virtue of the deliberative part of the rational part of the soul that manifests as the ability to deliberate about what actions would be beneficial and expedient in leading a life of virtue and eudaimonia.

Here (and in the trailing paragraphs of section seven, which some people fold into this section), he has a few more things to say about it:

- Practical wisdom is concerned with down-to-earth, human things, and things that it makes sense to deliberate about — that is, things that have a purpose that human action can influence (there’s no reason, for instance, to deliberate about whether to grow old or not).

- Practical wisdom requires knowledge of both universals and particulars.

In this respect, it is like Philosophy

(see section seven), though

Philosophy concerns itself with impractical-though-interesting things.

The “universals” and “particulars” bit has to do with the syllogism.

For example:

You can go wrong in practical wisdom by failing to know the truth about either the universal or the particular. For instance:All men are mortal (universal)

Socrates is a man (particular)

∴ Socrates is mortal (practical wisdom about Socrates!)

In this case, if you have faulty understanding of either the universal truth about swollen cans or of the particular truth about the can you’ve just opened, you’ll lack the important practical wisdom that will keep you from getting sick. Or, try on this anarchist syllogism:Cans that are swollen may contain rotten food that can make you sick (universal)

The food you’re about to eat came from a swollen can (particular)

∴ You may get sick if you eat it (practical wisdom about your future!)

You need the universal, the particular, and the logical process in order to get to the conclusion, and you can go wrong at any of these stages. Intuition will get you the universal, but it may take practical wisdom itself to get you the particular from which you can draw appropriate conclusions.Theft is wrong (universal)

Taxation is a variety of theft (particular)

∴ Taxation is wrong (practical wisdom) - Practical wisdom comes under different headings, depending on the sphere

in which it is exercised. For example:

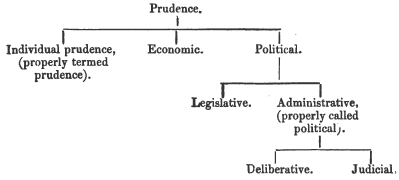

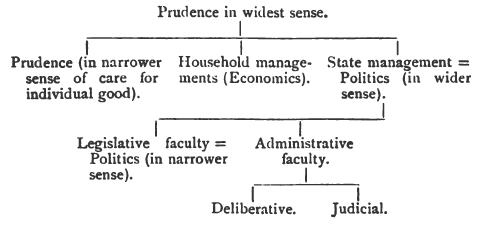

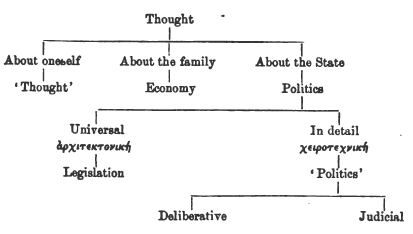

heading sphere prudence self-government domestic management home economics legislation the universal principles of politics deliberative government executive government; the carrying out in particular cases of the universals enacted by legislation judicial government

The varieties of practical wisdom, from R.W. Browne’s The Nicomachean Ethics of Aristotle ()

The varieties of practical wisdom, from J.H. Muirhead’s Chapters from Aristotle’s Ethics ()

The varieties of practical wisdom, from Alexander Grant’s The Ethics of Aristotle ()

- People who apply practical wisdom in their own lives are considered people of practical wisdom, while those who apply it to other peoples’ lives (for instance, the legislators, deliberators, and judges in the list above) “are considered meddlesome.” But Aristotle asks us to consider whether it might be impossible for most people to mind their own business if some people didn’t try to apply their wisdom to problems of the community, and whether it is possible to mind your own business without at the same time minding the business, at least to some extent, of those you interact with, either in your household or in the community at large.

- While it’s possible for a young person to be a savant with a genius understanding of something like mathematics, practical wisdom seems to be something that must be acquired through long experience. Aristotle thinks this is because expertise in mathematics largely requires an intellectual understanding of abstract universals, while practical wisdom requires actual encounters with real-life particulars. When you teach a young savant a mathematical truth, he or she grasps it as a truth immediately; but when you teach a truth of practical wisdom, the same student may have reason to be skeptical and to need to see that truth exemplified in real-life examples first before he or she can internalize it into his or her worldview.

- Practical wisdom concerns things of “common sense” — knowledge that like that gained via Intuition (see section six) is known but cannot be justified via logical deduction from other facts. However, knowledge gained by Intuition has to do with general, universal “first principles,” while the knowledge of practical wisdom has to do with particulars. The sense we use to gain this knowledge is the one we use when, for instance, we see a drawing of a triangle and think “that is a triangle” without actually measuring the angles and counting the sides. It is the sense that allows us to go from an observation to a particular fact, breaking out of the potentially endless loop of skeptical ratiocination to decide “aha! I know such-and-such about such-and-such, so there.”

Index to the Nicomachean Ethics series

Aristotle’s Nicomachean Ethics

- Introduction

- Book Ⅰ

- Book Ⅱ

- Book Ⅲ

- Book Ⅳ

- Book Ⅴ

- Book Ⅵ

- Book Ⅶ

- Book Ⅷ

- Book Ⅸ

- Book Ⅹ

- Bibliography