Here are a couple of newspaper articles that give a glimpse of how American Quakers addressed war tax resistance at the New York Yearly Meeting gathering at Lake George in , where “the tragic situation in Viet Nam” was high on the agenda:

The first excerpt comes from an article by Dee Wedemeyer from the Knickerbocker News:

A report published after the meeting called on members of the Society of Friends to exercise their consciences and offered support to those Quakers whose actions resulted in financial or personal loss.

“We call upon Friends to obey the Inner Light even when this means disobeying man’s laws, and to risk whatever penalties may be incurred,” said the report.

“We call upon Friends to examine their consciences concerning whether they cannot more fully dissociate themselves from the war machine by tax refusal or changing occupations.”

“We call upon Friends to urge that young men consider in conscience whether they can submit to a military system that commands to kill and destroy.”

“We call upon Friends Meetings to support acts of compromise [sic] by setting up Committees for Sufferings to keep close touch with deeply exercised Friends and their families who may need spiritual and material care because of their witness.”

So far, there has been no indication that any Friends will not pay their taxes, or refuse the draft or disobey “man’s laws.” But if any do they will be supported by other Friends.

“I’ve thought about it but I’m not persuaded that this is an effective way. I admire people if their conscience leads them to take that action,” says John Daniels, clerk of the Albany Society of Friends.

An Associated Press dispatch from , put it this way:

Quakers in the New York area have been encouraged to refuse to pay taxes or hold jobs that contribute to the war effort in Viet Nam. The Society of Friends office here made public a document or “testimony” approved at an annual meeting at Silver Bay on Lake George, N.Y.

Similar to the Peace Declaration of The Friends in 1660, the message was described as perhaps the “strongest message of the 20th century by a major body within the denomination.”

In the document, Quakers were promised financial help through special committees if they changed jobs or refused to pay taxes in protest against the war.

The new “testimony” warned Quakers that they may be facing a “supreme test” that could lead to persecution such as the sect suffered 300 years ago.

Entitled “Message to Friends on Viet Nam,” the document said members of the society must “stand forth unequivocally and at all costs to proclaim their peace testimony.”

Quakers were urged to express their concern over the war to lawmakers and the world community, and to “examine their consciences concerning whether they cannot more fully dissociate themselves from the war machine by tax refusal or changing occupations.”

The 72 Friends “meetings” or congregations in New York, northern New Jersey, and southern Connecticut were called upon to “support acts of conscience by setting up committees for sufferings…”

I also made note of this Lake George meeting in my entry. At that time I was unable to find an on-line copy of the “Message to Friends on Viet Nam,” but in renewing my search, I found that someone had uploaded a scan of the Friends Journal. That article didn’t get me any closer to the text I was hunting for, but it did include some other interesting items, including an article by Franklin Zahn on tax resistance, and another by Thomas Bassett about the New England Yearly Meeting that shows war tax resistance was on the agenda there too:

Tax Refusal, Law, and Order

by Franklin Zahn

In the President asked for a ten per cent surcharge on income taxes that might “continue for so long as the unusual expenditures associated with our efforts in Vietnam require higher revenues.” In words of Quaker simplicity, he was requesting a war tax. What ought Friends to do about specific levies for war?

First, of course, they can work to prevent such legislation, using the agency they have set up for such purposes — the Friends Committee on National Legislation — and using the opportunity to tell congressmen again that Friends favor de-escalation rather than the escalation the new taxes are designed to permit.

If the President’s request becomes law, Friends may then pay under protest. This situation might loosely be compared to that of a young man who joins the Army under protest: voicing his convictions is better than not voicing them, but it’s not a satisfactory solution. After paying a war tax Friends may then through regular channels claim a refund, and although in the past this has never been granted on the basis of conscience, a number of California taxpayers plan to make a common court case. Here the analogy might be to the young man who goes to court to get released from the Army — again not a very hopeful approach. However, the young man is entitled by law to request exemption in the first place; unfortunately for Friends as taxpayers, no such legal choices are available to them. Years ago Pacific Yearly Meeting suggested legislation embodying conscientious-objector provisions in Federal tax laws, and today some Friends are still considering such proposals, but for the foreseeable future, pacifists will have no legal tax alternatives.

Further, for most Friends there is not even a possible illegal alternative for their tax dollars, for if not paid as ordered, the dollars are frequently levied from bank accounts which unfortunately most Friends in their affluence today have. It is as though a pacifist refused to bayonet an enemy and several strong men held the weapon in his hands and jabbed it for him. The choice is not whether to participate in war or not, but whether to do so willingly or to drag one’s feet.

Many see a refusal to pay taxes voluntarily as only a protest. Now it is true that we can designate any act we engage in as a protest against something. We can fast and announce that our purpose is to protest the war. A vigil, a march, a meeting, or a handing out of educational material can be a protest if so designated. Even the young Friend who refused to carry the bayonet could refuse as a protest. But we are not necessarily protesting anything when we refuse to do that which for us is wrong. We refuse to steal not as a protest against burglary — with consideration of how “effective” we may or may not be — but simply because for us stealing is wrong. Similarly, a Friend may refuse to pay taxes voluntarily, not in protest but because he feels he must not participate in war.

In Southern California’s Quarterly Meeting there are many individuals and three Meetings refusing to pay voluntarily the seven per cent war tax on telephone bills. I do not know which are consciously doing this as a “protest” and which see it as part of the Friends’ code of conduct or way of life. When Claremont Meeting, in its public statement, said that in refusing to pay it was following a precedent in Friends’ peace testimony, two newspapers used the term “protest” in their very good coverage and one did not. All three papers quoted the portion of the statement that said, “Those of us who refuse to pay taxes which go to support war also are willing to accept the legal consequences of this refusal…”

Such willingness, along with complete openness, is an important part of any “civil” or, as one Friend terms it, “courteous” disobedience. It might also be called “orderly” disobedience, for, contrary to the usual linking together of “law and order,” in these days of riots the two words are not necessarily related. The war in Vietnam is considered by many Americans to be lawful, but to Vietnamese villagers the aftermath of a bombing raid would hardly appear orderly. On the contrary, the refusal to pay taxes for such chaos may be unlawful, but when the decision is made openly, arrived at in the usually slow and quiet manner of Friends’ group decisions, and explained in nonevasive language with a willingness to accept penalties, it may be very orderly indeed.

Franklin Zahn, member of Claremont (Calif.) Meeting, free-lance writer, and compiler of the recent leaflet “Early Friends and War Taxes,” first refused the telephone excise tax in , during the Korean War, and had his telephone disconnected. (In , the Internal Revenue Law was amended, permitting telephone companies to refer unpaid taxes to IRS.) In he read this paper to Pacific Yearly Meeting’s session on civil disobedience.

New England Yearly Meeting

Reported by Thomas Bassett

Quakerism is uneasy everywhere in the face of long-continuing violence, “distress of nations, and perplexity whether on the shores of Asia or in the Edgware Road.” Friends’ answers to problems of the Vietnam war and urban riots have ranged from evangelical mission to Quaker action. Evangelical Friends eschew mere human “manipulation” and expect peace only when Christ reigns in human hearts. Philadelphia and Baltimore Yearly Meetings, reinforced by AFSC and FCNL staffs in their midst, approved minutes to send medical aid to North Vietnam against the law if it could not be changed.

New England Friends were, as usual, in the middle of this scale. The clerk opened the first plenary session with William Penn’s words on evangelism: “They were changed men themselves before they went out to change others.” The last, eight-hour session approved a minute to oppose the President’s war surtax and urged its members to earnest consideration of whether they can conscientiously pay war taxes.

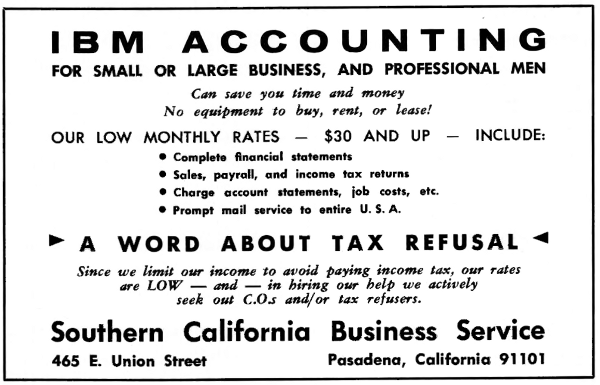

And take a look at this advertisement from the back pages: